Constructor Patterns in Rust: From Basics to Advanced Techniques

Some of my friends are learning Rust, and they are coming from languages like C++ or Java. One thing that one of them told me is:

It’s crap, the new function only has one declaration. You can’t declare it based on the number of arguments like in C++ or Java, but on the other hand, there’s no problem with macros…

After answering with a lot of messages about the different ways to make good constructors in Rust, I decided to write this blog about it.

Why do we need constructors

A constructor in general has multiple usages:

- Instantiation : It is the most common usage : creating an instance from smaller pieces, like a

struct, anenumor aclass(for C++/Java developers).

Primitive types like integers or floats already have a native syntax for construction (e.g., 42 for an integer, true or false for a boolean). More complex types, especially composite types like structures, tuples, or arrays, require a mechanism or syntax to initialize themselves.

Encapsulation : It’s about invariant and control. Deciding what value are valid or what relation the structure should hold. The goal is to avoid any invalid state, typically achieved through data hiding and encapsulation.

Placement : In C++, the constructor also determines where in memory the object is initialized.

Move Semantic: Copy and Clone

In Rust, there are 2 traits for duplicating a value: Clone and Copy.

Copy: Types whose values can be duplicated simply by copying bits. is a marker trait that impliesClone. By marker trait, I mean there is no logic in theCopytrait itself the definiton is:pub trait Copy: Clone { }. The compiler ensure that the type implementsCloneand that it can be bit copied. All the logic for duplicating a value is in theClonetrait.

Type that have have a field that have an indirection layer in memory such as Box, Vec, String, HashMap, HashSet, etc can’t be Copy, just Clone.

Copy constructor are done implicitly, and are fast..

let value = 42;

let value2 = value; // implicit copy because it is cheap to do.

…and Clone constructor are done explicitly, and are slower because the object is generaly heavier to duplicate.

let value = "hello".to_owned(); // 1 memory allocation, and can't be bit copied

let value2 = value.clone(); // explicit clone, 2 memory allocations

For comparison, everythings is implictely cloned in C++, there no distinction between Copy and Clone.

This mean you can accidentally clone a vector or a string, which can be expensive, without realizing it.

You can impl manually the Clone trait for a type, or you can use the derive macro that will implement it automatically for you:

// derive macro:

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

struct MyI32 {

x: i32

}

// or manually:

impl Clone for MyI32 {

fn clone(&self) -> Self {

MyI32 { x: self.x }

}

}

impl Copy for MyI32 {}

Struct Instantiation in Rust

#[derive(Debug, Clone, Default)]

pub struct Person

{

pub age: i32,

pub name: String,

pub hobbies: Vec<String>,

}

If you want to create/instantiate a new Person, you can just use the struct literal syntax

.

let bobby = Person { age: 42, name: "Bobby".to_owned(), hobbies: vec!["programming".to_owned()] };

Even better, you can create another person based on bobby for all the missing fields.

let alice = Person { name: "Alice".to_owned(), .. bobby };

This is the struct update syntax described in the Rust book.

Doing this will move bobby’s fields, so the moved ones will not be available after it:

let bobby = Person { age: 42, name: "Bobby".to_owned(), hobbies: vec!["programming".to_owned()] };

let alice = Person { name: "Alice".to_owned(), .. bobby };

dbg!(&bobby.name); // ok because Alice constructor has her own name

// dbg!(&bobby.hobbies); // error: borrow of moved value: `bobby.hobbies`. It was moved to Alice

dbg!(&bobby.age); // ok, because the type `i32` is `Copy`, so it was copied, not moved

If you still want to be able to use bobby, one easy way is to clone it:

let alice = Person { name: "Alice".to_owned(), .. bobby.clone() };

dbg!(&bobby); // ok

Ok great, this is great for satisfying the first point instantiating new structure, but it completely breaks the encapsulation. Anyone can create a new person with a negative age:

pub struct Person

{

pub age: i32, // should be >= 0 and <= 150

pub name: String,

}

// somewhere in the main function...

let alice = Person { age: -100, name: "Alice".to_owned() };

alice.age = -200;

Even after initialization, anyone can read, and edit the age field.

Encapsulation

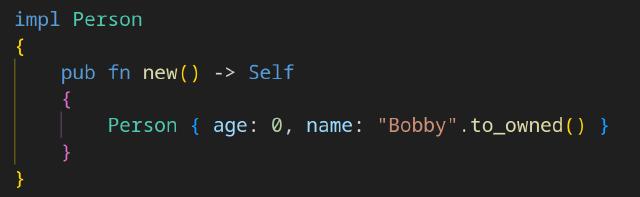

If you are coming from Java/C#/C++ the answer is simple: just make the field private, and write a constructor to be able to initialize the struct, and add some getter/setter to control the access to the field. Let’s focus on the constructor part for the moment:

pub struct Person

{

// the fields are no longer public

age: i32,

name: String,

}

impl Person

{

pub fn new(age: i32, name: String) -> Self

{

Self { age, name }

}

}

Right now, even if we are not validating the age, the new method is the only way to construct a person, so if any logic should occur to validate the input, it should happen here.

Because the field are private by default (absence of pub), nobody outside the current module can read/write them. The same apply for initializing the struct using the Person{ age:42, name:"Alice".to_owned() } syntax.

Notice that the constructor is just a plain function in Rust. It doesn’t have any special syntax, you can take its address, and even write a constructor inside a trait/interface.

To make sure the instance of the person we are building is valid, we can have a fallible constructor that returns an Option<Self> or a Result<Self,MyConstructorErrorType> if you want to specify why the struct can’t be constructed with the current parameter. (If the parameters are costly to compute, like the string name, we can also return them properly in the error of the result).

impl Person

{

pub fn try_new(age: i32, name: String) -> Option<Self>

{

if age < 0 || age > 150 { return None };

Some(Self { age, name })

}

}

let alice = Person::try_new(42, "Alice".to_owned()).expect("it should be good");

A lot of constructors/functions in the standard library are fallible, and their names start with try_

.

Fallible constructor is something that can’t be directly done in C++/Java purely by using the constructor, because constructors in those languages can’t fail. Surely you can throw an exception. But you can also emulate a fallible constructor by making the constructor private, and write a static function to be able to initialize the class, and add some getter/setter to control the access to the field:

Example in Java this time:

public class Person {

private int age;

private String name;

// Private constructor prevents direct instantiation

private Person(int age, String name) {

this.age = age;

this.name = name;

}

// Static factory method: returns null or throws if invalid

public static Person tryCreate(int age, String name) {

if (age < 0 || age > 150) {

return null; // or throw new IllegalArgumentException("Invalid age");

}

return new Person(age, name);

}

}

// Usage

Person alice = Person.tryCreate(42, "Alice");

if (alice == null) {

System.out.println("Invalid person");

}

or you can use the Optional type instead of returning null on failure for a cleaner approch:

public class Person {

private int age;

private String name;

private Person(int age, String name) {

this.age = age;

this.name = name;

}

public static Optional<Person> tryCreate(int age, String name) {

if (age < 0 || age > 150) {

return Optional.empty();

}

return Optional.of(new Person(age, name));

}

}

Ok let’s go back to Rust. We can have constructors that auto-correct invalid input, or constructors that panic on invalid input.

impl Person

{

// Note: the naming of the constructor is just for the example, idk how to name it properly

pub fn new_auto_corrected(mut age: i32, name: String) -> Self

{

age = age.max(0).min(150);

Self { age, name }

}

/// Panics on invalid input

pub fn new(age: i32, name: String) -> Self

{

Self::try_new(age, name).expect("it should be good") // panic on None

}

}

let alice = Person::new_auto_corrected(42, "Alice".to_owned());

let alice = Person::new(42, "Alice".to_owned());

It’s fine to have helper functions or constructors that can panic, as long as:

- It is clearly documented,

- The underlying mechanism (here, the

try_newfunction/constructor) is public. This allows others to build a non-failing abstraction on top that won’t panic.

We just need to add a few getter/setter and we are done with encapsulation:

impl Person

{

pub fn age(&self) -> i32 { self.age }

// The result type can also be a `bool` in this case,

// but a `Result` make it explicit that this function can fail

// Ok returns the original mutable reference to self for

// method chaining . It is not required, but I like it

pub fn set_age(&mut self, age: i32) -> Result<&mut Self,()>

{

if age < 0 || age > 150 { return Err(()) };

self.age = age;

Ok(())

}

pub fn name(&self) -> &str { &self.name }

pub fn rename(&mut self, name: String) -> &mut Self { self.name = name; self }

}

let mut p = Person::new();

p.set_age(42).unwrap().rename("Alice");

Ok now it’s time to address the rude original critique

It’s crap, the new function only has one declaration. You can’t declare it based on the number of arguments like in C++ or Java, but on the other hand, there’s no problem with macros…

The point of the argument is about convenience : you can’t have multiple new functions in Rust.

Ho boy, you have no idea how wrong you are. You want conveniance, i’ll give you some.

In Java, you would probably write:

public class Person

{

private int age;

private String name;

public Person(int age, String name) {

this.age = age;

this.name = name;

}

// Redefining another constructor

public Person(String name) {

this.age = 0;

this.name = name;

}

// Delegate to another existing constructor

public Person(int age) {

this(age, "Unknown");

}

// + getter and setter

}

It’s better to delegate all constructors to only one constructor, that way only this one needs to check the invariants.

If you try the same in Rust it will fail:

impl Person {

pub fn new(age: i32, name: String) -> Self {

Self { age, name }

}

pub fn new(name: String) -> Self {

Self { age: 0, name }

}

pub fn new(age: i32) -> Self {

Self::new(age, "Unknown".to_string())

}

}

You can’t have multiple function with the same name new, there is no overloading in Rust. (at least not like that).

The solution is simple: be more creative, and use different names:

impl Person {

pub fn new(age: i32, name: String) -> Self {

Self { age, name }

}

pub fn from_name(name: String) -> Self {

Self::new(0, name)

}

pub fn from_age(age: i32) -> Self {

Self::new(age, "Unknown".to_string())

}

}

Large Structure

Traditionnal constructors where you list all the fields are simple to use when they have few parameters, but it is not convenient when you have a lot of them:

pub struct Person {

name: String,

age: u32,

email: String,

phone: String,

address: String,

city: String,

country: String,

}

impl Person {

pub fn new(

name: String,

age: u32,

email: String,

phone: String,

address: String,

city: String,

country: String,

) -> Self {

Self {

name,

age,

email,

phone,

address,

city,

country,

}

}

}

// How convenient... We can do better

let p = Person::new(

"John Doe".to_string(),

42,

"john.doe@example.com".to_string(),

"1234567890".to_string(),

"On the street because the rent are expensive".to_string(),

"Anytown".to_string(),

"USA".to_string()

);

Note: I use a lot of String type for the example, but it’s not the best choice for a real-world application for modeling a country, an email… Those should have their own type that validates the value.

If you have a structure with a lot of fields, it becomes barely usable:

- It’s hard to read the code,

- The constructor is long,

- The field order really matters if you don’t want to accidentally swap the city and the country,

- And it’s easy to make a mistake.

And if, in the future, you want to add a new field, you will have to update all the caller. Imagine doing this as a library/crate developer, you can’t ask every user to update their code because you decided to add a new field.

Constructors in this case are not the best way to initialize it. It’s better to use a builder pattern.

Builder Pattern

If you have a large structure that needs to verify invariants, it’s better to use a builder pattern. Typically, you can initialize a Person from another structure that has the same fields in public.

#[derive(Default)]

pub struct PersonBuilder {

// Notice the public fields

pub name: String,

pub age: u32,

pub email: String,

pub phone: String,

}

pub struct Person {

name: String,

age: u32,

email: String,

phone: String,

}

impl Person

{

pub fn new(builder: PersonBuilder) -> Self { builder.build() }

}

impl PersonBuilder

{

pub fn build(self) -> Person {

Person { name: self.name, age: self.age, email: self.email, phone: self.phone }

}

}

let p = Person::new(

PersonBuilder

{

age:42,

name:"John Doe".to_string(),

email:"john.doe@example.com".to_string(),

phone:"1234567890".to_string()

}

);

// or

let p = PersonBuilder{

age:42,

name:"John Doe".to_string(),

email:"john.doe@example.com".to_string(),

phone:"1234567890".to_string()

}.build();

// or:

let p = Person::new(PersonBuilder{age:42, name:"John Doe".to_string(), .. Default::default()});

This works well because:

- all fields are now named, and the order doesn’t matter

- it respects encapsulation for the

Personstruct.

Right now this is an infallible builder, it always returns a Person, but we can make it fail if needed and return an Option<Person> or a Result<Person, Error>.

Notice how, by making the same structure public, we can now use the struct literal to initialize the builder.

It is also possible to define some kind of profile that will edit multiple parameters at once:

impl PersonBuilder

{

pub fn avoids_technology(self) -> Self { Self { phone: "no phone".to_owned(), email: "no email".to_owned(), .. self, } }

}

let p = PersonBuilder::new().name("Kevin").avoids_technology().age(7).build();

Maybe this example is a bit too simple, but it is really useful to be able to quickly define new profiles like that, think about a structure describing some complex configuration.

Some crates like wgpu use this pattern a lot to initialize all kinds of structures using the name XDescriptor

:

let instance = wgpu::Instance::new(

&wgpu::InstanceDescriptor // right here :)

{

#[cfg(not(target_arch = "wasm32"))]

backends: wgpu::Backends::PRIMARY,

#[cfg(target_arch = "wasm32")]

backends: wgpu::Backends::GL,

..Default::default()

}

);

(Example taken from Learn Wgpu )

Convenient Setter By Value

We can even make some convenient methods on the builder to initialize each field

impl PersonBuilder

{

pub fn new() -> Self { Self::default() }

pub fn age(self, age: i32) -> Self { Self { age, .. self } }

pub fn name(self, name: String) -> Self { Self { name, .. self } }

// other possible syntax

pub fn email(mut self, email: String) -> Self { self.email = email; self }

// or even making the string creation more convenient

pub fn phone(self, phone: impl Into<String>) -> Self { Self { phone: phone.into(), .. self } }

}

let p = PersonBuilder::new()

.age(42)

.name("John Doe".to_owned())

.phone("1234567890") // No `to_owned()` because of Into

.build();

Backward Compatibility

If we need to add more fields later, without restricting the API, we can mark the struct non_exhaustive :

#[non_exhaustive]

#[derive(Default)]

pub struct PersonBuilder {

// Notice the public field

pub name: String,

pub age: u32,

pub email: String,

pub phone: String,

}

This means that we can’t use the struct literal outside of the current crate to initialize the builder, because new fields can be added in the future.

You can still use the struct update syntax:

PersonBuilder{age:42, .. PersonBuilder::new()};

or the convenience methods to set the fields.

PersonBuilder::new()

.age(42)

.name("John Doe".to_owned())

.phone("1234567890");

That way, even if we add new fields in the future, it will not break the API and old code will still work without any change.

Builder Traits Are Useless?

If we want, we can even make a trait for builder:

pub trait Builder<T> {

fn build(self) -> T;

}

impl Builder<Person> for PersonBuilder

{

fn build(self) -> Person {

Person { name: self.name, age: self.age, email: self.email, phone: self.phone }

}

}

impl Person

{

// Accept any type that implements the Builder trait,

// not just PersonBuilder, even if we don't need more

// than one builder type.

pub fn new(builder: impl Builder<Self>) -> Self { builder.build() }

}

pub trait FallibleBuilder<T> {

type Error;

fn try_build(self) -> Result<T, Self::Error>;

}

But wait! This looks exactly like the From and TryFrom traits in the standard library!

So we can remove these unnecessary Builder and FallibleBuilder traits and use these traits instead:

impl From<PersonBuilder> for Person {

fn from(builder: PersonBuilder) -> Self {

// ...

}

}

impl Person

{

pub fn new(value: impl Into<Person>) -> Self { value.into() }

}

The inconvenience is that it is hard to know what we can pass to the new function by just looking at the type signature.

Merging the Builder and the Struct

If the struct have a default value, we can avoid writing a builder and use the same struct for the builder!

#[derive(Default)]

pub struct Person

{

age: i32,

name: String,

}

impl Person

{

pub fn new() -> Self { Self::default() }

pub fn with_age(self, age: i32) -> Self { Self { age, .. self } }

pub fn set_age(&mut self, age: i32) -> &mut Self { self.age = age; self }

pub fn age(&self) -> i32 { self.age }

pub fn with_name(self, name: String) -> Self { Self { name, .. self } }

// + name(_) and set_name(_)...

}

let p = Person::new().with_age(42).with_name("John Doe");

This works well if the default value is not too complex to compute, and if the logic for editing every field with_age()/with_name(), etc… is not too complex.

Notice how fn with_age(self, age: i32) -> Self and fn set_age(&mut self, age: i32) -> &mut Self are very similar, and we can use the same logic for both. It’s maybe a bit annoying to write the same logic twice, and to have 2 names almost similar for the same thing, except the first one is called by value and the second one is by reference.

The From and Into trait

The From and Into traits are a way to convert a type into another type. The conversion must be infallible/can’t fail, without any loss of information.

For example From<u8> for u32 is possible because it’s a lossless conversion/integer promotion, but From<u32> for u8 is not possible, because it can’t convert a number that is too big to fit in a u8. Instead you need to use the as keyword for casting: 42u32 as u8. (Maybe I should cover more about convertion in a future post.)

For small types, it’s convenient to use the From and Into traits, and generic friendly.

From a code perspective, you just need to implement From trait, and the Into trait will be automatically implemented for you as stated in the std:

From trait description:

Into trait description:

One should avoid implementing

Intoand implementFrominstead.

struct MyCustomI32(i32);

impl From<i32> for MyCustomI32 { fn from(value: i32) -> Self { MyCustomI32(value) } }

impl From<MyCustomI32> for i32 { fn from(value: MyCustomI32) -> Self { value.0 } }

let x = MyCustomI32::from(42);

Another version of the From/Into traits is the TryFrom

/TryInto

traits, that allow converting a type into another type, but can fail and return a custom error.

Placement New

Currently Rust doesn’t support placement new. I guess this is one of the situations where C++ constructors are more versatile than Rust ones.

All values in Rust are always created on the stack, and moved to the heap if necessary, even if the value guarentee to be on the heap (e.g. Box::<i32>::new(42) will be created on the stack, and moved to the heap. Not a big deal for an i32, but it is problematic for [i32; 65536] because it can cause a stack overflow. Some workaround exists).

There is an RFC for it https://github.com/PoignardAzur/rust-rfcs/blob/placement-by-return/text/0000-placement-by-return.md , but I can’t tell more about it.

Other Useful Links

Rust Book : Defining and Instantiating Structs

Idiomatic Rust (for C++ Devs): Constructors & Conversions

, it also cover more Copy constructor.

Conclusion

Rust offers multiple powerful approaches to constructors, each suited for different scenarios:

For simple structs: Use new() functions with clear, descriptive names like from_name() when you need different initialization patterns.

For validation: Implement fallible constructors (try_new()) that return Option<Self> or Result<Self, Error> to handle invalid input gracefully.

For complex structs: Use the builder pattern to handle many fields while maintaining readability and backward compatibility. Method chaining like with_age() is also possible.

For conversions: Leverage From/Into traits for type conversions and TryFrom/TryInto for fallible conversions.

While Rust doesn’t have traditional constructor overloading like C++/Java, these patterns provide even more flexibility and safety. The key is choosing the right approach for your specific use case rather than trying to force one-size-fits-all solutions.

Remember: good constructor design in Rust is about providing clear, safe, and idiomatic ways to create valid instances of your types.

I hope you have learned something from this blog post! Seeya!

Other Idea that don’t work…

It is not possible to unify the set_age and with_age functions (and it is overkill):

pub trait SetAge

{

fn set_age(self, age: i32) -> Self;

}

impl SetAge for &mut Person

{

// error: method `set_age` has an incompatible type for trait

fn set_age(&mut self, age: i32) -> &mut Self { self.age = age; self }

// ^^^^^^^^^ expected `Person`, found `&mut Person`

}

impl SetAge for Person

{

fn set_age(mut self, age: i32) -> Self { self.age = age; self }

}

let mut p = Person::new().set_age(42); // by value

assert_eq!(p.age(), 42);

p.set_age(43); // by mutable reference

assert_eq!(p.age(), 43);